Acute Mountain Sickness

In my last post I briefy mentioned my failed Mt. Shasta attempt. Today I will go into greater detail about what happened and what precautions I’ll take going forward.

At 14,162 feet tall, Mt. Shasta is the second highest mountain in the Mazamas 16 Northwest Peaks challenge. It’s a nearly six hour drive from Portland, making it the most distant of the sixteen peaks in terms of travel, with Mt Shuksan a close second at five and half hours and Mt Olympus at a paltry five hours. We took the Hotlum Bolam Glacier route, the easiest route on the north side of the peak. It proved to be a much less crowded alternative to the south facing Avalanche Gulch route.

I had spent the week prior in Yellowstone with my family, sleeping at an average elevation of 6,500 feet. After making the drive down to the North Gate trailead, we established basecamp at 6,800 feet and spent the night. We set off at 0900 the next morning and had established high camp at 10,000 feet around 1300 that same day. The plan was to make a late alpine start for the summit at 0400 the next morning. I figured this would provide ample time to acclimitize for the final push. I went to bed early at 1800 to get as much sleep as possible.

Two hours later I woke up with a headache and severe nausea. I vomited my half-digested chicken fried rice dinner into the same bag that I had used to rehydrate it. Despite my best efforts to lay still and to go back to sleep, my heart rate continued to race at nearly a hundred beats per minute.

I drifted off into a fitful sleep before my alarm woke me up at 0300. I was able to eat some oatmeal and to keep it down, but ultimately decided to stay at high camp in order to avoid threatening the likelihood of summiting for the rest of the group. After a successful summit, the team returned to camp at 1400 and we began the long trip back to Portland.

Although I didn’t summit that day, I did learn some important lessons that should allow me to summit on the next attempt. The first (and biggest) one was that acetazolamide, like all drugs, loses its efficacy over time. The pills that I brought with me were nearly three years old and well past their expiration date. Not only was the medicine’s overall effect muted, the prophlactic increase in respiration rate was far less than what it would have otherwise been with a fresh prescription. The duration of the respiration rate increase was also substantially reduced. I’ve found that the effects of new acetazolamide can last 24-36 hours after each dose. Comparatively, the effects of my expired medication lasted less than 12 hours after initial ingestion. These limitations meant that I wasn’t able to aclimitize as rapidly as needed.

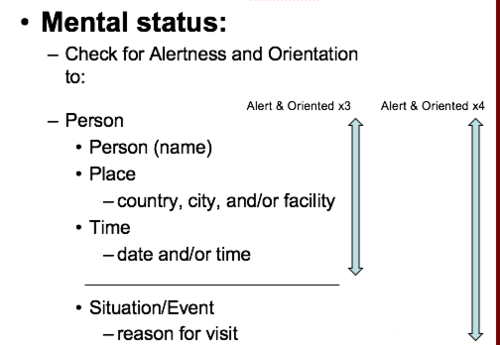

My second lesson learned was that I should be more measured in my response AMS, and rely on AO4 (Alert and Oriented x 4) as an objective means to assess the impacts of altitude.

From what I was told after they returned, nearly the entire team suffered from nausea and headaches by the time that they reached the summit. Luckily they remained lucid and coordinated, completing the summit and returning safely. Given the widespread nature of these symptoms, bringing ibroprofun to treat the swelling from AMS headaches and emetrol for the nausea could go a long way for addressing immediate discomfort. Both medications are non-drowsy, over-the-counter solutions that might help others actually enjoy their brief stay at the summit before descending. This isn’t to say that they should be relied on for long periods of time, as they could easily conceal the development of more serious conditions like HACE (High Altitude Cerebral Edema) and HAPE (High Altitude Pulmonary Edema) if used to combat symptoms for more than 24 hours.

The third lesson learned was the negative effect that caffeine and alcohol can have towards acclimitization. While I personally abstained from both substances well in advance of the climb, there was one other climber who stayed in the camp with me on summit day due to AMS. They said that while they don’t normally get AMS, they had consumed copious amounts of coffee on the drive down from Portland. Caffeine actively constricts the blood vessels in your head and can worsen the headaches and nausea caused by AMS. Alcohol for its part reduces red blood cell production. Red blood cells are responsible for transporting oxygen throughout the body. Part of the acclimitization process known as erythrocytosis involves bone marrow increasing red blood cell production to allow oxygen to be more efficiently delivered to your body. Alcohol hinders erythrocytosis and slows acclimitization.

To summarize, my major lessons were to only use fresh acetezolamide, treat physiological symptoms with pallative mediction while monitoring overall mental alertness, and to avoid caffeine and alcohol before and during the climb. I hope these lessons will allow me to eventually complete a summit of Mount Shasta. I’ll be excited to give it another shot.

Photo by Rohit Tandon on Unsplash

Comments